Susanne Isabel Bockelmann

![]() Druckgrafik

Druckgrafik

![]() Malerei

Malerei

![]() Zeichnungen

Zeichnungen

![]() Installationen

Installationen

![]() Glasfenster

Glasfenster

![]() Projekte

Projekte

Volkhard Böhm

Susanne Isabel Bockelmann - Pictures of Yearning and Antagonism

Art is surely nothing but expression of our dreams. (Franz Marc)

"Wolves" from the series "Bears and Horses", a linocut from 1997, has the size of a frieze: it is almost one meter high and two and a half meter wide. A female figure, defenceless and naked, is sitting in the middle, ecstatically contorted, her head turned backwards, looking upwards, hands and arms stretched out widely. Face, breasts and arms are forming a line, which is leading upwards out of the picture. Could that be a gesture of supplication? A wolf, crouching at the right side, picks up this line in a parallel, but now it is leading downwards between the woman’s thighs. On the left side we find a striding creature in appearance of a sphinx, mixture of horse, wolf and/or fox, seeming harmless, unless there were no fifth leg, or phallus. Both animals are connected to the woman by two almost circular planes, the right one resembling a flaw.

|

| From the series "Bears and Horses - Wolves" Linocut, 240 x 93 cm, 1997 |

The picture is full of metaphoric as most of the pictures of Susanne Bockelmann. Man and animal, which are symbols, are inseparably united; the circular planes are standing for this fact. In mythology and dream interpretation, the wolf ready to jump in front of the woman’s lap represents by its ferocity the aggressive sexual desires, meanwhile the calmly striding horse-wolf creature beside the woman’s head, who is facing it, may stand for the intellectual taming of these brutish sexual energies and the desire for a restrained inner life.

Therefore this picture could be allegory for the human tension between desire and menace, between devotion and self-control. The metaphors of Susanne Bockelmann, and sometimes her figures, too, are never unequivocal; often a mystery remains, full of surprises and yearnings as life itself.

The female artist, born in Hameln on the Weser, studied from 1979 to 1984 at the technical college of design, first in Nürnberg, then in Hamburg. She started out with a realistic and figurative conception of art. In her thesis she tried to catch the destinies of homeless persons by means of drawing their physiognomies. Hereby she met borders, which made her search for new modes of expression.

Experiences and impulses from abstract art of the classical modern age lead to an extremely changed style. Almost orgiastic she plunged into a frenzy of colours and forms. Many paintings were created, where single forms in pure, often unmixed, contrasted colourfulness are whirling around or standing next to each other. Abstract forms, which give rise to associations of well known motives, e.g. a boat. Changing to graphic arts from 1984 on, she obviously searched and found the means and possibilities of expression to realize her artistic intention in the symbiosis of realistic figurativeness and formal abstraction by merging her artistic and design experiences so far, and the technique of wood- and linocut.

But she remains true to the attraction of abstraction, mainly in small-format high prints of forms, which are covering or transparently overlapping themselves. These folios have a impressively atmospheric profundity.

Forms and figures are flat and big on the painting, the dimension of deepness is sacrificed. In the colour printings, rich colours are crashing onto each other, alleviating transitions are only there, where forms are overlapping in a glazing way. The faces are almost big, round, mask-like due to their simplification, but therefore of a universal validity; the ecstatic bodies are in unrestricted devotion with strange contortions and anglings. Wide opened eyes and emphasized hands with spread-out fingers come along, conspicuous picture elements, which are standing for attention, defence or imploring. That creates an elementary and archaic effect and so even the smallest form is becoming monumentally, like man and animal ornaments of historical stone paintings on cave walls. Later on the knowledge of the expressionistic woodcut art surely is supporting , as well as the concise forms of Matisse’s cut-outs and the abstractions and deep symbolism of the German HAP Grieshaber. In particular the latter is very close to her, formally and in content.

She loves the simple form, which she develops at first in mind and afterwards through an ostensible telling hand with pen and knife. So her forms are keeping - beside all monumentality - an easiness.

Her way of working is spontaneously and controlled at same time. The picture is coming into being in mind, is drawn directly onto the wood or lino plate, is preserved or changed during the cutting, forms and planes are pulled together and compressed, details are added or left out. This process is not finished until the manual printing, with the possible modulation of the colour, by stronger or softer pressure of a fold, the handle of her woodcut knife or the ball of her thumb. Especially by looking at her large-format folios, we learn that this creative act is not only an intellectual but also a physical effort.

The large form is dominating, and often the large planes, torn open by delicate and seeming timidly drawn contours, which give life to the figures. Neighbouring planes are only partially modelled by bars, which are left behind due to the parallel cutting. Different motives are additively overlying each other during the colour printing. The colour is used precisely varied through the printing. Its pureness and its contrast are similar to her way of working in her painting. As well she keeps the collage technique, which she often uses for joining the forms and figures. On one hand she is entirely graphic designer the way she is drawing the lines and choosing form and colours, on the other hand her tender and sensitive way to print the colour planes shows her painting intention. She utilizes lino, chipboards and wooden boards, often with bark on it, as printing carrier. She uses the wooden blocks on both sides. The printing technique is almost only taken for small-format paper folios, otherwise for white fleece paper and seldom for textile. That way she creates single folios, no intended series. Folios, which are showing similarities, are combined afterwards.

Already in the small-format abstract cuts, where forms are overlapping each other like in collages, she goes beyond the pure aesthetical-designing pretension. Often we find forms, which evoke metaphorical associations. The boat-form e.g., which as boat or ship is metaphor for longing and hope, but also for farewell and return.

|

|

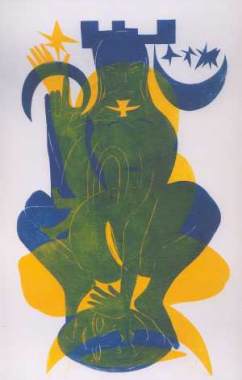

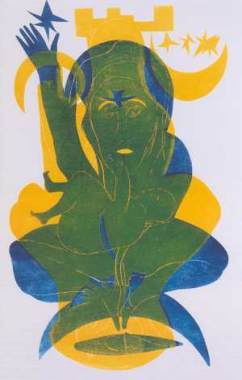

| From the series "Christ I" Linocut, 96x185 cm |

From the series "Christ II" Linocut, 96x185 cm |

The most remarkable fact of the larger graphics of Susanne Bockelmann surely is her autonomous iconography, anchored in the traditional cultural asset, which is supplied by the mythology of different people and cultures ("La Serenissima, Venice" and La Zia de Venere, Venice", two linocuts of Venice, 1998, or "Innuit", linocut, 1997), by religion ("Christ", 1998; series "Bildstöcke [Blocks] - Clara von Assisi I + II", 2000), but also by fairy-tales and fables. Always she puts motives with economy.

The relation between man and animal is getting more and more important. While she is often conceiving the animal figures in a statuesque way, her crouching or ecstatically stretched or contorted female figures are expressive, especially in their gestures. The figures stay outlined, but become more voluminous. The formats are becoming larger. Now the monumentality of the figures gets the monumental format. But despite of this monumentality it remains a lyrical general tone and often a mystical enigma. Besides the mythology, obviously pictures out of the dream world are appearing on these folios. Fairy-tales, myths and the dream world have in common that they are nourished on conscious- and unconsciousness, which are reciprocally causing and pervading each other.

The animals - at first it is the fox (series "Foxes and other creatures", 1993), then follows the wolf, after a journey to Canada it is the bear (series of bears, 1996), the horse, the elephant (2000) and also the owl and the bird - here are more inspired by the world of dreams than by fable, fairy-tale or mythology. Usually they are animals, who are uniting ferocity, power and strength from mythology (wolf, horse, bear, elephant) with animal sexual urge from dream interpretation (wolf, horse, elephant). And on the other side, there is the naked female figure, often full of bursting voluptuousness up to vital sexuality, lied down, perhaps also devoted, squatted down, ecstatically contorted towards the animal. That attracts attention on these folios: male strength and female sensuousness in context and the yearning for love, for bodily love in between, and the more intellectual resistance against these elementary forms of love. For owl and bird are also symbols for that love in dream interpretation.

From approximately 2000 on there is a reduction in motives, the world of dreams is left, the mystical reference remains, which she is using freely. A lyrical general tone increases, to the debit of the epic. And I think that a pondering, existentialistic tendency is entering the motives.

The figures are often melting into one another, enclosed figures are hiding or revealing in the big form, cut out of the extended form of the wooden board ("Europe in the shadow of Taurus", 2000, or in the shown wood block from the series "Blocks", 2000).

In her high-format folios, cut out of boards, more as tall as man, figures and forms are not only piling, one upon the other, up "to the sky", they also seem to stagger spatially into the depth. The figures are stretching, the feet are pushing off, the arms and hands are trying to burst the picture upwards. In the oblong formats the human figures are tied up in associating animal figures. Longing all over, for freedom, but also for security, for boundless love. And it is this language of form, being generally valid in its reduction, which is leading the individual iconography and motives to a general valid statement. In a convincing way Susanne Isabel Bockelmann creates pictures of the eternal mystery of mankind, the inner strife between desire and self-determination and the permanent trial of liberation from animal elementary compulsions in a mystical reality, free of any kind of moralizing. With that these are pictures of man suffering on himself and his eternal aspiration to self-deliverance.

[...]

Translation of an article published in the German magazine

GRAPHISCHE KUNST. Internationale Zeitschrift für Buchkunst und Graphik.

Neue Folge: Heft 2/2004. Edition Kurt Viesel, Memmingen (ISSN 0342-3158).

| 25. November 2011 |